Trinity's Place in First Ward's History

The following article appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of The Trinity Voice

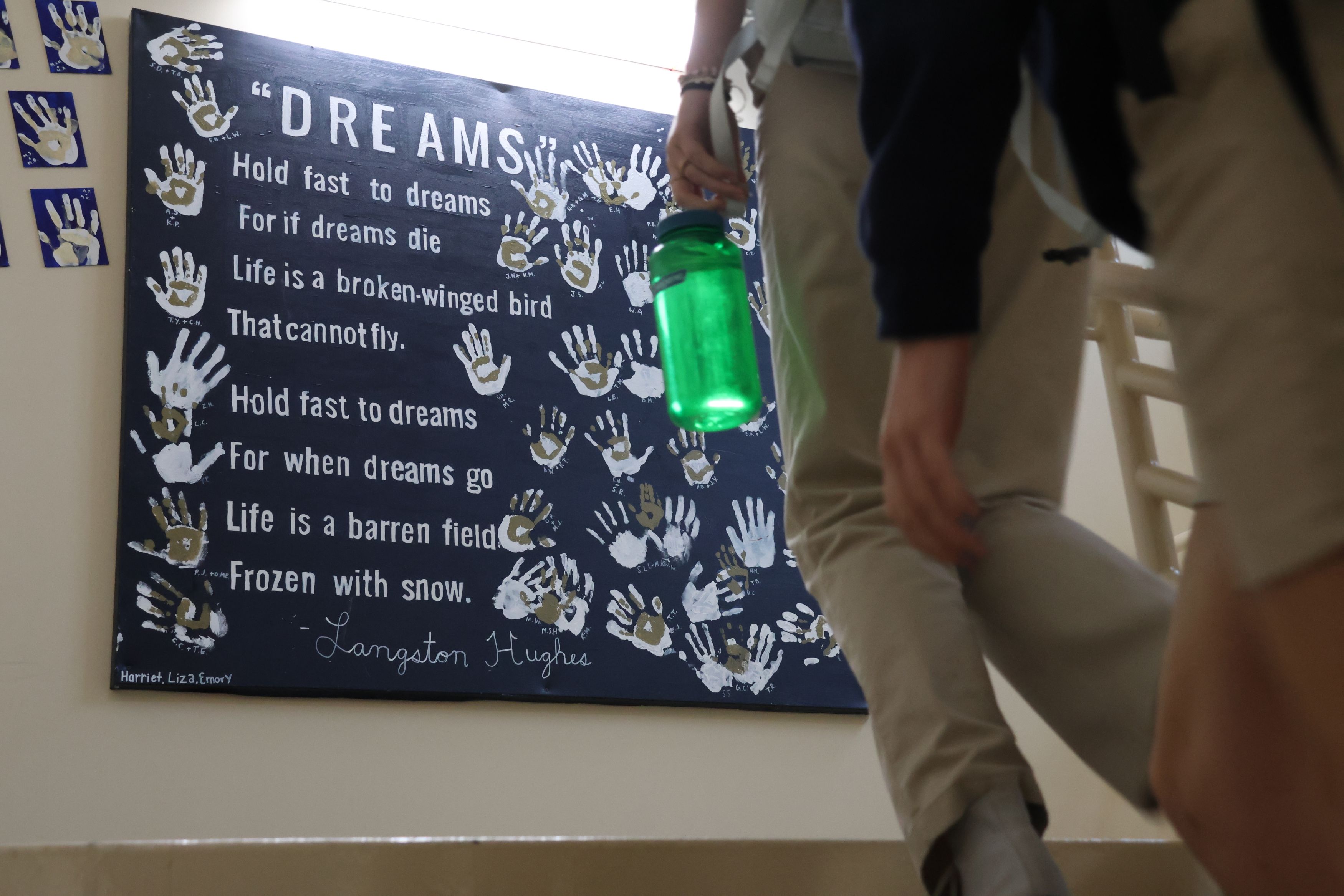

When Trinity students climb the third-floor stairs, past the wall art featuring Langston Hughes’ poem “Dreams,” they are steps away from where the poet himself once dreamed.

The artwork is, by coincidence, the closest thing to a historical marker of First Ward’s past. There are no similar callbacks to the church that once stood where the carpool lane begins, or the community that was created - and later destroyed - where students now make their way to ImaginOn.

“History is not the past - we live inside various histories,” said Greg Jarrell, an author and community organizer who sat on a panel discussion in January at Trinity’s annual Freedom Fete. The conversation, moderated by Director of Diversity, Equity, and Belonging Ayeola Elias, explored Charlotte’s past and how that history might shape the city’s future.

“It’s important to know (those histories) so that we can understand the story that we’re living,” Jarrell said.

First Ward's Beginnings

Trinity planted itself in First Ward in the late 1990s as the neighborhood was changing - a constant in First Ward’s history. The neighborhood was created because of Charlotte’s growth and change in the post-Civil War years. With a booming population of more than 4,000, the city was divided in 1869 into four political districts - “wards” - extending out from Trade and Tryon Streets.

Dr. Tom Hanchett, Charlotte’s leading community historian, said First Ward was arguably the center city’s most racially and economically diverse neighborhood at the time. White and Black residents, Hanchett said, lived side-by-side for many blocks.

But as the 19th Century gave way to the 20th, the neighborhood began segregating into all-Black or all-White sections, and by the 1930s, First Ward and nearby Second Ward were the centers of Charlotte’s Black population, Hanchett said.

“So Much History”

As First Ward was emerging as a majority Black neighborhood, it became home to another example of segregation in the broader community.

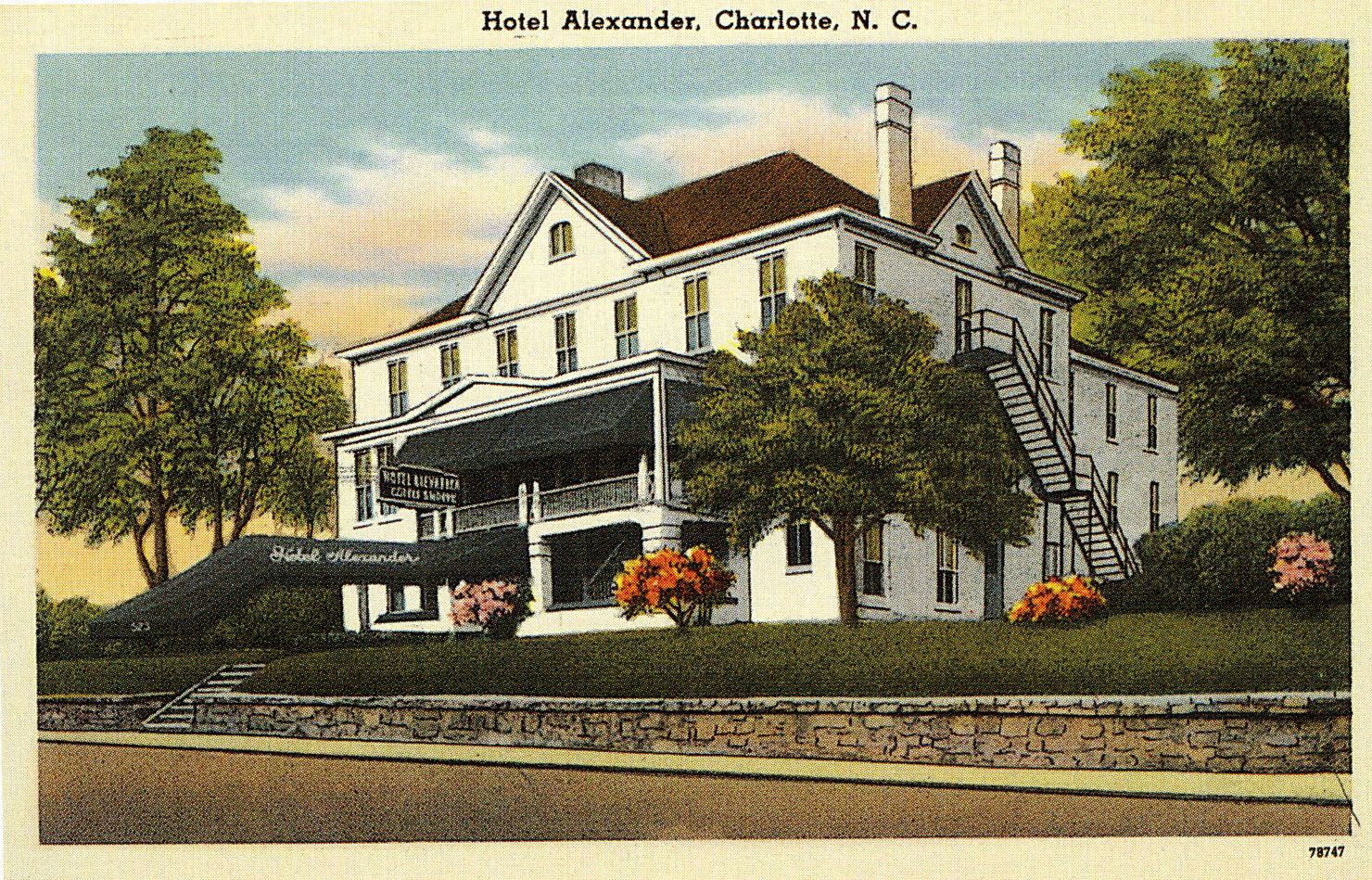

Located at the corner of 9th and McDowell Streets, the Hotel Alexander opened in December 1947 and was billed as the city’s first hotel for Black guests.

Owned by local physician John Eugene Alexander, the Alexander was envisioned as “a center for (Black) activity as well as a first-rate hotel,” according to a Charlotte Observer story on its opening.

The hotel was one of the Charlotte stops listed in “The Negro Travelers’ Green Book” of businesses that would serve Black customers as they navigated segregated America. At the Alexander, those customers included leading Black figures of the era. It was where Langston Hughes checked in and read his poetry to a private audience during a 1950 Charlotte visit.

“Sam Cook stayed there; Nat ‘King’ Cole stayed there,” recalled Arthur Griffin, who grew up on 6th Street in First Ward.

Griffin, a long-time civic leader in Charlotte and current member of the Mecklenburg County Board of Commissioners, participated in the Freedom Fete panel in January.

Peeling back another layer of the history behind Trinity’s location, Griffin shared that before it was a hotel, the Alexander was the location of the Florence Crittenton Home for unwed mothers.

Behind the Alexander, at the corner of 9th and Myers Street - where Trinity’s driveway begins - was Griffin’s childhood church, Gilfield Baptist Church, which moved in the 1950s and went on to become one of Charlotte’s largest congregations - University Park Baptist Church, now called The Park Church.

“There’s so much history,” Griffin said at Freedom Fete. “It’s important for us - and not just African Americans - to know African American history because African American history is American history.”

Beginning of the End

The threads of First Ward began pulling in the mid-20th century as urban renewal arrived a few blocks over in the all-Black Brooklyn community of Second Ward.

Greg Jarrell’s book, “Our Trespasses: White Churches and the Taking of American Neighborhoods,” chronicles the destruction of Brooklyn as the city began buying property and demolishing homes that were deemed “slums.” An iconic photo of the city’s campaign shows then-Mayor Stan Brookshire in December 1961 taking a sledgehammer to the porch of a home to initiate the razing of Brooklyn.

“We’re scared about where to go,” Brooklyn resident Fanny Woodard told The Charlotte Observer. She and more than 1,000 other families were displaced as nearly 1,500 homes and more than 200 businesses were leveled.

Not a single new residential unit was built in their place.

By 1967, the city trained its bulldozers on First Ward and other Black communities near downtown, applying the same “slum” label to those neighborhoods as it did to Brooklyn.

The federal government, meanwhile, observed the toll renewal was taking and mandated that Charlotte devise a plan for relocating displaced residents. The result was Earle Village - a sprawling 409-unit public housing project in First Ward spread across 11 city blocks.

Hanchett, the community historian, said Earle Village did not solve any of the relocation challenges. “In fact, they tore down more existing housing in First Ward (to make way for Earle Village) than were built back,” he said.

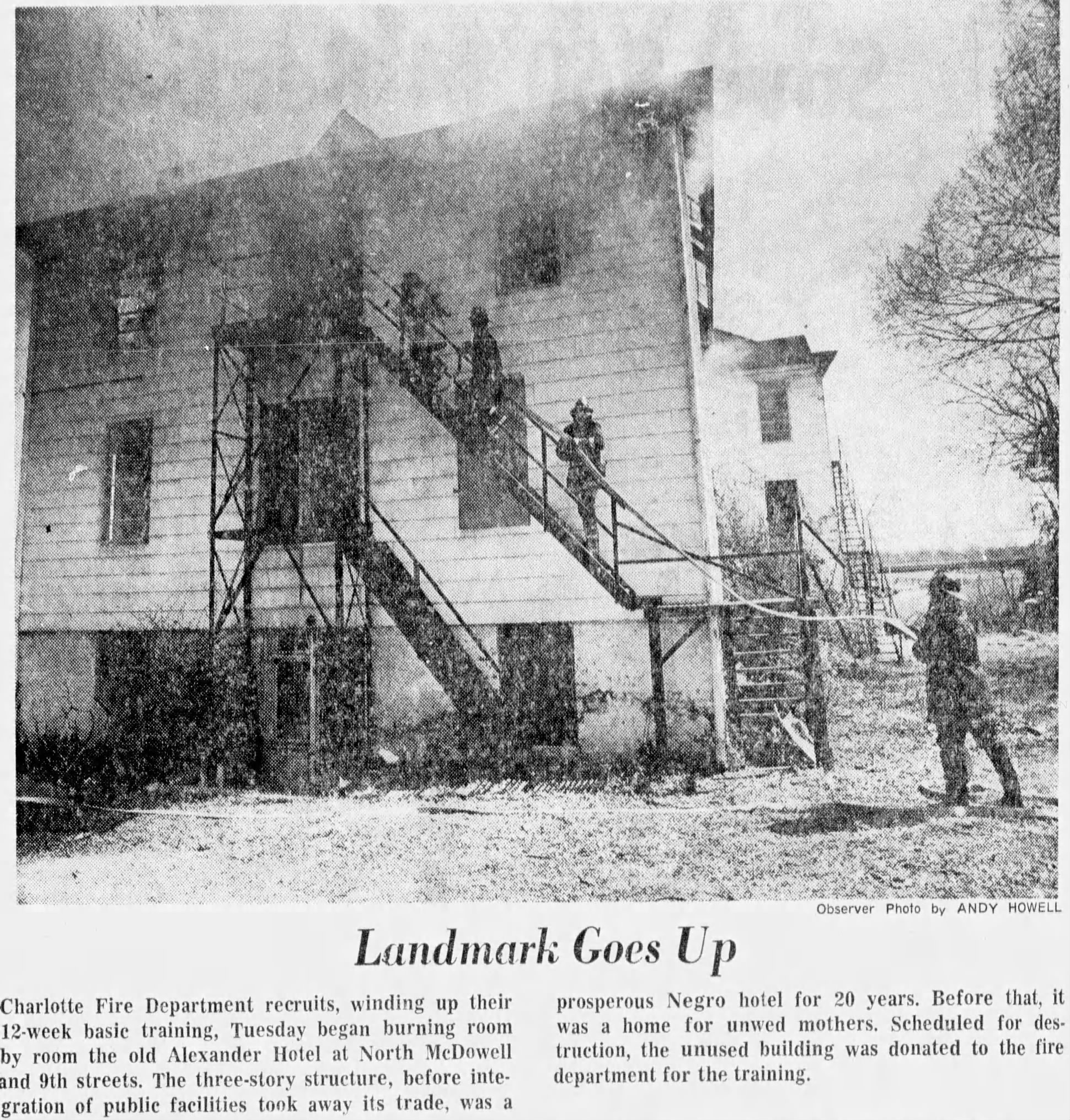

With Earle Village in place, and after a lawsuit by First Ward residents who said the city had not provided adequate replacement housing, the urban renewal of First Ward marched on. Among the casualties was the Hotel Alexander, which the city purchased for less than $46,000 ($268,000 in 2025 dollars). By then, the Alexander had fallen by the wayside. Civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s that ordered the integration of businesses ironically made the hotel unnecessary.

“The big bands, the entertainers, the traveling men - the mainstays of its business - haven’t been back,” said a Charlotte Observer article. The homes on the opposite side of McDowell Street were already boarded up to make way for what would become the Brookshire Freeway section of I-277, named for the mayor who took the sledgehammer to Brooklyn.

Once shuttered, the hotel was burned down in 1973 as part of a Charlotte Fire Department training exercise. In the rubble was a cornerstone with an inscription: “Florence Crittenton Home, March 10, 1905.”

The Path Forward

The final toll of Charlotte’s urban renewal: 11,115 housing units destroyed, including Arthur Griffin’s home on 6th Street and 466 other homes in First Ward.

“Some folks, especially for communities such as First Ward, experienced deep and traumatic loss,” Jarrell said at Freedom Fete, “and that history is much more alive than it is for the rest of us.”

It didn’t take long for Earle Village to absorb the same “slum” tag that befell Brooklyn. A 1993 Charlotte Observer article called it a “crime-plagued cluster of generational poverty.”

In his book, Jarrell said that viewpoint overlooks the city’s own role in the neighborhood’s lack of quality of life by not investing in its upkeep and infrastructure, and the landlords who rented out housing that was below building code.

The 1990s marked a turning point for First Ward and Earle Village.

Hanchett said it had become clear that the urban renewal method of wholesale demolition “didn’t work, didn’t create healthy new neighborhoods.”

Government agencies and others began embracing a mixed-income approach to housing. “That was so radical at that (time),” Hanchett said.

In 1993, Congress created the HOPE VI program for cities to replace massive public housing projects such as Earle Village with mixed-income redevelopment. Charlotte won a HOPE VI grant in the program’s first year, and in 1995, the first bulldozers moved in on Earle Village. In a scene reminiscent of the sledgehammering of Brooklyn, then-Mayor Richard Vinroot and federal Housing and Urban Development Secretary Henry Cisneros smiled as the first buildings crumbled under bulldozers.

Just as the creation of Earle Village caused a loss of housing in First Ward, its death left nearly half of its residents displaced. “For folks who lived there, there’s still some anger,” Hanchett said.

Still, Charlotte was hailed as a national leader in mixed-income housing. Earle Village was replaced by First Ward Place, which included apartments for low-income residents, while on neighboring 8th and 9th Streets, new single-family homes and townhomes began rising out of the ground with the help of investments from NationsBank, the predecessor of Bank of America.

“By and large, it has worked,” Hanchett said, as housing was built for diverse economic levels.

This surge of First Ward redevelopment caught the attention of a group of families looking to open an Episcopal School in Charlotte that represented the community’s diversity. In 1997, they approached the city to purchase the property at 9th and McDowell Streets, which had been vacant since the razing of the Hotel Alexander nearly a quarter-century earlier.

“We are more and more excited about what is happening in First Ward,” Trinity’s founding Board of Trustees chairman, Ted Rast, told the City Council.

New Challenges

More than 60 years on from the beginning of urban renewal, Charlotte continues to grapple with where people can live.

Arthur Griffin told the audience at Freedom Fete that modern housing segregation in Charlotte is more along class lines than racial lines, citing his native First Ward as an example.

“I grew up here, but can’t live here today,” Griffin said. “Look at the cost of the homes.”

Similar housing pressures are finding their way to Dorothy Counts-Scoggins’ childhood community of Biddleville-Smallwood on Charlotte’s Historic West End. Biddleville emerged from the urban renewal era as the city’s oldest surviving Black neighborhood. Today, homes that were built in the post-World War II baby boom are selling for more than half a million dollars, and newly-built homes are in the multi-million dollar range.

“It’s changing like a lot of other communities in Charlotte,” Counts-Scoggins said at Freedom Fete. “I don’t use the word ‘gentrification.’ I use the word ‘transition.’”

Counts-Scoggins made international headlines in 1957 when she tried to integrate the all-white Harding University High School. The hostile reaction from her classmates was a galvanizing moment for the civil rights movement.

She moved back to Biddleville in 2002 and sees community involvement - and an obligation by newcomers to learn the neighborhood’s history - as essential to its preservation.

“What we have to do is to learn to work together,” she said. “We can preserve it together.”

Jarrell echoed the importance of personal choices in reversing the lingering impacts of urban renewal, encouraging the audience at Freedom Fete to, for example, shop for groceries in a different neighborhood.

“If we don't want to live in a segregated city, then we can make some choices to desegregate our lives,” he said.

But because it was policies that brought about urban renewal and its ill effects, Jarrell said, it will take new policies to undo them.

“Our city has been engineered for segregation,” he said, “and if you want something different, then you’re going to have to reverse-engineer it” through zoning policies, transportation planning, and other measures.

Griffin was optimistic that the combination of personal choices and political decisions by leaders such as himself would put Charlotte on a different path.

“We are all in this together as a Charlotte family,” he said. “I think we can get there. But (we’re) going to have to put forth a personal commitment and effort to make Charlotte work.”